"Tho' personally unknown, still we can assure you that you will find yourself no stranger among us; that genius with which you have been so signally gifted, and which your pen has directed with such consummate skill in delineating every passion and sympathy and peculiarity of the human mind, has secured to you a passport to all hearts; whilst your happy personifications, and apt illustrations, pointing at every turn a practical and fruitful moral, have rendered your name as familiar to us as household words.

"In testimony of our respect and high regard, and as a slight, tho' thankful, tribute to your genius, we request that you will name as early a day as may suit your convenience, to meet us in this City at a public dinner, where, as elsewhere, it will be our pride and pleasure to express our gratitude to you for the many such intellectual feasts you have so often spread before us.

"S. JONES.

W. T. MCCOSEN.

SAM. R. BETTS.

JNO. DUCK.

THEODORE SEDGWICK.

WM. SAML. JOHNSON.

D. S. KENNEDY.

JAMES G. KING.

HENRY BREVOORT.

CHARLES MARCH.

ANTH. BARCLAY.

J. PRESCOTT HALL.

JAS. GALLATIN.

JOHN A. KING.

WILLIAM KENT.

DAVID C. COLDEN.

G. G. HOWLAND.

JAMES J. JONES.

JACOB B. LE ROY.

M. C. PATERSON.

"WASHINGTON IRVING.

PHILIP HONE.

DANL. B. TALLMADGE.

H. S. JONES.

MURRAY HOFFMAN.

HENRY CARY.

CH. KING.

W. C. BRYANT.

W. B. ASTOR.

MATURIN LIVINGSTON.

HAMILTON FISK.

JAS. D. OGDEN.

M. H. GRINNELL.

WM. H. ASPINNALL.

EDWARD CURTIS.

EDWARD JONES.

WM. C. RHINELANDER.

ABM. SCHIRMERSTRONG.

THO. M. LUDLOW.

FITZGREENE HALLECK.

C. W. AUGTS. DAVIS."

"NEW YORK, January 26, 1842.

"SIR,

"Mr. Colden, one of our number, will have the honor of presenting this invitation, and is charged with the agreeable duty of presenting their congratulations on your arrival. We shall expect thro' him your kind acceptance of this invitation, and your designation of the day when it may suit your convenience to attend.

"RORT. H. MORRIS.

PHILIP HONE.

JOHN W. FRANCIS.

J. W. EDMONDS.

DANL. B. TALLMADGE.

C. W. AUGTS. DAVIS.

JOHN C. CHEESMAN.

WM. H. MAXWELL.

DUNCAN C. PELL.

PROSPER M. WETMORE.

A. M. COUZENS.

JOHN R. LIVINGSTON, JR.

WM. B. DEAR.

JAMES M. SMITH, JR.

WM. GRANDIN.

WADDELL.

D. G. GREGORY.

M. H. GRINNELL.

"WM. STARR MILLER.

F. A. TALLMADGE.

CHAS. W. SANAFORE.

GEO. P. MORRIS.

SAML. P. LYMAN.

WM. TURNER.

H. INMAN.

A. G. WONG.

R. FAYERWEATHER.

W. R. NORTHALL.

MARTIN HOFFMAN.

J. BECKMAN FISH.

JAMES PHALEN.

W. H. APPLETON.

S. DRAPER, JR.

F. W. EDMONDS.

JNO. S. BARTLETT.

JNO. INMAN.

"To CHARLES DICKENS, Esq., etc."

III

SECOND IMPRESSIONS

1842

His second letter, radiant with the same kindly warmth that gave always charm to his genius, was dated from the Carlton-hotel, New York, on 14 February, but its only allusion of any public interest was to the beginning of his agitation of the question of international copyright. He went to America with no express intention of starting this question in any way; and certainly with no belief that such remark upon it as a person in his position could alone be expected to make, would be resented strongly by any sections of the American people. But he was not long left in doubt on this head. He had spoken upon it twice publicly, "to the great indignation of some of the editors here, who are attacking me for so doing, right and left." On the other hand all the best men had assured him, that, if only at once followed up in England, the blow struck might bring about a change in the law; and, yielding to the agreeable delusion that the best men could be a match for the worst in such a matter, he urged me to enlist on his side what force was obtainable, and in particular, as he had made Scott's claim his war cry, to bring Lockhart into the field. I could not do much, but what I could was done.

Three days later he began another letter; and, as this will be entirely new to the reader, I shall print it as it reached me, with only such omission of matter concerning myself as I think it my duty, however reluctantly, to make throughout these extracts. There was nothing in its personal details, or in those relating to international copyright, available for his Notes; from which they were excluded by the two rules he observed in that book, the first to be altogether silent as to the copyright discussion, and the second to abstain from all mention of individuals. But there can be no harm here in violating either rule, for, as Sydney Smith said with his humorous sadness, We are all dead now.

"Carlton-house, New York: Thursday, February Seventeenth, 1842. . . . As there is a sailing-packet from here to England to-morrow which is warranted (by the owners) to be a marvellous fast sailer, and as it appears most probable that she will reach home (I write the word with a pang) before the Cunard steamer of next month, I indite this letter. And lest this letter should reach you before another letter which I dispatched from here last Monday, let me say in the first place that I did dispatch a brief epistle to you on that day, together with a newspaper, and a pamphlet touching the Boz ball; and that I put in the post-office at Boston another newspaper for you containing an account of the dinner, which was just about to come off, you remember, when I wrote to you from that city.

"It was a most superb affair; and the speaking admirable. Indeed, the general talent for public speaking here, is one of the most striking of the things that force themselves upon an Englishman's notice. As every man looks on to being a member of Congress, every man prepares himself for it; and the result is quite surprising. You will observe one odd custom -- the drinking of sentiments. It is quite extinct with us, but here everybody is expected to be prepared with an epigram as a matter of course.

"We left Boston on the fifth, and went away with the governor of the city to stay till Monday at his house at Worcester. He married a sister of Bancroft's, and another sister of Bancroft's went down with us. The village of Worcester is one of the prettiest in New England. . . . On Monday morning at nine o'clock we started again by railroad and went on to Springfield, where a deputation of two were waiting, and everything was in readiness that the utmost attention could suggest. Owing to the mildness of the weather, the Connecticut river was 'open,' videlicet not frozen, and they had a steamboat ready to carry us on to Hartford; thus saving a land-journey of only twenty-five miles, but on such roads at this time of year that it takes nearly twelve hours to accomplish! The boat was very small, the river full of floating blocks of ice, and the depth where we went (to avoid the ice and the current) not more than a few inches. After two hours and a half of this queer travelling we got to Hartford. There, there was quite an English inn; except in respect of the bed rooms, which are always uncomfortable; and the best committee of management that has yet presented itself. They kep us more quiet, and were more considerate and thoughtful, even to their own exclusion, than any I have yet had to deal with. Kate's face being horribly bad, I determined to give her a rest here; and accordingly wrote to get rid of my engagement at Newhaven, on that plea. We remained in this town until the eleventh: holding a formal levee every day for two hours, and receiving on each from two hundred to three hundred people. At five o'clock on the afternoon of the eleventh, we set off (still by railroad) for Newhaven, which we reached about eight o'clock. The moment we had had tea, we were forced to open another levee for the students and professors of the college (the largest in the States), and the townspeople. I suppose we shook hands, before going to bed, with considerably more than five hundred people; and I stood, as a matter of course, the whole time. . . .

"Now, the deputation of two had come on with us from Hartford; and at Newhaven there was another committee; and the immense fatigue and worry of all this, no words can exaggerate. We had been in the morning over jails and deaf and dumb asylums; had stopped on the journey at a place called Wallingford, where a whole town had turned out to see me, and to gratify whose curiosity the train stopped expressly; had had a day of great excitement and exertion on the Thursday (this being Friday); and were inexpressibly worn out. And when at last we got to bed and were 'going' to fall asleep, the choristers of the college turned out in a body, under the window, and serenaded us! We had had, by the bye, another serenade at Hartford, from a Mr. Adams (a nephew of John Quincey Adams) and a German friend. They were most beautiful singers: and when they began, in the dead of the night, in a long, musical, echoing passage outside our chamber door; singing, in low voices to guitars, about home and absent friends and other topics that they knew would interest us; we were more moved than I can tell you. In the midst of my sentimentality though, a thought occurred to me which made me laugh so immoderately that I was obliged to cover my face with the bedclothes. 'Good Heavens!' I said to Kate, 'what a monstrously ridiculous and commonplace appearance my boots must have, outside the door!' I never was so impressed with a sense of the absurdity of boots, in all my life.

"The Newhaven serenade was not so good; though there were a great many voices, and a 'reg'lar' band. It hadn't the heart of the other. Before it was six hours old, we were dressing with might and main, and making ready for our departure; it being a drive of twenty minutes to the steamboat, and the hour of sailing nine o'clock. After a hasty breakfast we started off; and after another levee on the deck (actually on the deck), and 'three times three for Dickens,' moved towards New York.

"I was delighted to find on board a Mr. Felton whom I had known at Boston. He is the Greek professor at Cambridge, and was going on to the ball and dinner. Like most men of his class whom I have seen, he is a most delightful fellow -- unaffected, hearty, genial, jolly; quite an Englishman of the best sort. We drank all the porter on board, ate all the cold pork and cheese, and were very merry indeed. I should have told you, in its proper place, that both at Hartford and Newhaven a regular bank was subscribed, by these committees, for all my expenses. No bill was to be got at the bar, and everything was paid for. But as I would on no account suffer this to be done, I stoutly and positively refused to budge an inch until Mr. Q---- should have received the bills from the landlord's own hands, and paid them to the last farthing. Finding it impossible to move me, they suffered me, most unwillingly, to carry the point.

"About half past 2, we arrived here. In half an hour more, we reached this hotel, where a very splendid suite of rooms was prepared for us; and where everything is very comfortable, and no doubt (as at Boston) enormously dear. Just as we sat down to dinner, David Colden made his appearance; and when he had gone, and we were taking our wine, Washington Irving came in alone, with open arms. And here he stopped, until ten o'clock at night." (Through Lord Jeffrey, with whom he was connected by marriage, and Macready, of whom he was the cordial friend, we already knew Mr. Colden; and his subsequent visits to Europe led to many years' intimate and much enjoyed intercourse.) "Having got so far, I shall divide my discourse into four points. First, the ball. Secondly, some slight specimens of a certain phase of character in the Americans. Thirdly, international copyright. Fourthly, my life here, and projects to be carried out while I remain.

"Firstly, the ball. It came off last Monday (vide pamphlet).

"At a quarter past 9, exactly "(I quote the printed order of proceeding), "we were waited upon by 'David Colden, Esquire, and General George Morris;' habited, the former, in full ball costume, the latter in the full dress uniform of Heaven knows what regiment of militia. The general took Kate, Colden gave his arm to me, and we proceeded downstairs to a carriage at the door, which took us to the stage door of the theatre: greatly to the disappointment of an enormous crowd who were besetting the main door, and making a most tremendous hullaballoo. The scene on our entrance was very striking. There were three thousand people present in full dress; from the roof to the floor, the theatre was decorated magnificently; and the light, glitter, glare, show, noise, and cheering, baffle my descriptive powers. We were walked in through the centre of the centre dress-box, the front whereof was taken out for the occasion; so to the back of the stage, where the mayor and other dignitaries received us; and we were then paraded all round the enormous ball-room, twice, for the gratification of the many-headed. That done, we began to dance -- Heaven knows how we did it, for there was no room. And we continued dancing until, being no longer able even to stand, we slipped away quietly, and came back to the hotel. All the documents connected with this extraordinary festival (quite unparalleled here) we have preserved; so you may suppose that on this head alone we shall have enough to show you when we come home. The bill of fare for supper, is, in its amount and extent, quite a curiosity.

"Now, the phase of character in the Americans which amuses me most, was put before me in its most amusing shape by the circumstances attending this affair. I had noticed it before, and have since, but I cannot better illustrate it than by reference to this theme. Of course I can do nothing but in some shape or other it gets into the newspapers. All manner of lies get there, and occasionally a truth so twisted and distorted that it has as much resemblance to the real fact as Quilp's leg to Taglioni's. But with this ball to come off, the newspapers were if possible unusually loquacious; and in their accounts of me, and my seeings, sayings, and doings on the Saturday night and Sunday before, they describe my manner, mode of speaking, dressing, and so forth. In doing this, they report that I am a very charming fellow (of course), and have a very free and easy way with me; 'which,' say they, 'at first amused a few fashionables;' but soon pleased them exceedingly. Another paper, coming after the ball, dwells upon its splendour and brilliancy; hugs itself and its readers upon all that Dickens saw; and winds up by gravely expressing its conviction, that Dickens was never in such society in England as he has seen in New York, and that its high and striking tone cannot fail to make an indelible impression on his mind! For the same reason I am always represented, whenever I appear in public, as being 'very pale;' 'apparently thunderstruck;' and utterly confounded by all I see. . . . You recognize the queer vanity which is at the root of all this? I have plenty of stories in connection with it to amuse you with when I return.

"Twenty-fourth February.

"It is unnecessary to say . . . . that this letter didn't come by the sailing packet, and will come by the Cunard boat. After the ball I was laid up with a very bad sore throat, which confined me to the house four whole days; and as I was unable to write, or indeed to do anything but doze and drink lemonade, I missed the ship. . . . I have still a horrible cold, and so has Kate, but in other respects we are all right. I proceed to my third head: the international copyright question.

"I believe there is no country, on the face of the earth, where there is less freedom of opinion on any subject in reference to which there is a broad difference of opinion than in this. . . . There! -- I write the words with reluctance, disappointment, and sorrow; but I believe it from the bottom of my soul. I spoke, as you know, of international copyright, at Boston; and I spoke of it again at Hartford. My friends were paralysed with wonder at such audacious daring. The notion that I, a man alone by himself, in America, should venture to suggest to the Americans that there was one point on which they were neither just to their own countrymen nor to us, actually struck the boldest dumb! Washington Irving, Prescott, Hoffman, Bryant, Halleck, Dana, Washington Allston -- every man who writes in this country is devoted to the question, and not one of them dares to raise his voice and complain of the atrocious state of the law. It is nothing that of all men living I am the greatest loser by it. It is nothing that I have a claim to speak and be heard. The wonder is that a breathing man can be found with temerity enough to suggest to the Americans the possibility of their having done wrong. I wish you could have seen the faces that I saw, down both sides of the table at Hartford, when I began to talk about Scott. I wish you could have heard how I gave it out. My blood so boiled as I thought of the monstrous injustice that I felt as if I were twelve feet high when I thrust it down their throats.

"I had no sooner made that second speech than such an outcry began (for the purpose of deterring me from doing the like in this city) as an Englishman can form no notion of. Anonymous letters; verbal dissuasions; newspaper attacks making Colt (a murderer who is attracting great attention here) an angel by comparison with me; assertions that I was no gentleman, but a mere mercenary scoundrel; coupled with the most monstrous misrepresentations relative to my design and purpose in visiting the United States; came pouring in upon me every day. The dinner committee here (composed of the first gentlemen in America, remember that) were so dismayed, that they besought me not to pursue the subject, although they every one agreed with me. I answered that I would. That nothing should deter me. . . . That the shame was theirs, not mine; and that as I would not spare them when I got home, I would not be silenced here. Accordingly, when the night came, I asserted my right, with all the means I could command to give it dignity, in face, manner, or words; and I believe that if you could have seen and heard me, you would have loved me better for it than ever you did in your life.

"The New York Herald, which you will receive with this, is the Satirist of America; but having a great circulation (on account of its commercial intelligence and early news), it can afford to secure the best reporters. . . . My speech is done, upon the whole, with remarkable accuracy. There are a great many typographical errors in it; and by the omission of one or two words, or the substitution of one word for another, it is often materially weakened. Thus I did not say that I 'claimed' my right, but that I 'asserted' it; and I did not say that I had 'some claim,' but that I had 'a most righteous claim' to speak. But altogether it is very correct."

Washington Irving was chairman of this dinner, and having from the first a dread that he should break down in his speech, the catastrophe came accordingly. Near him sat the Cambridge professor who had come with Dickens by boat from Newhaven, with whom already a warm friendship had been formed that lasted for life, and who has pleasantly sketched what happened. Mr. Felton saw Irving constantly in the interval of preparation, and could not but despond at his daily iterated foreboding of I shall certainly break down: though, besides the real dread, there was a sly humour which heightened its whimsical horror with an irresistible drollery. But the professor plucked up hope a little when the night came, and he saw that Irving had laid under his plate the manuscript of his speech. During dinner, nevertheless, his old foreboding cry was still heard, and "at last the moment arrived; Mr. Irving rose; and the deafening and long-continued applause by no means lessened his apprehension. He began in his pleasant voice; got through two or three sentences pretty easily, but in the next hesitated; and, after one or two attempts to go on, gave it up, with a graceful allusion to the tournament and the troop of knights all armed and eager for the fray; and ended with the toast CHARLES DICKENS, THE GUEST OF THE NATION. There! said he, as he resumed his seat amid applause as great as had greeted his rising, There! I told you I should break down, and I've done it!" He was in London a few months later, on his way to Spain; and I heard Thomas Moore describe at Rogers's table the difficulty there had been to overcome his reluctance, because of this break-down, to go to the dinner of the Literary Fund on the occasion of Prince Albert's presiding. "However," said Moore, "I told him only to attempt a few words, and I suggested what they should be, and he said he'd never thought of anything so easy, and he went and did famously." I knew very well, as I listened, that this had not been the result; but as the distinguished American had found himself, on this second occasion, not among orators as in New York, but among men as unable as himself to speak in public, and equally able to do better things, he was doubtless more reconciled to his own failure. I have been led to this digression by Dickens's silence on his friend's break-down. He had so great a love for Irving that it was painful to speak of him as at any disadvantage, and of the New York dinner he wrote only in its connection with his own copyright speeches.

"The effect of all this copyright agitation at least has been to awaken a great sensation on both sides of the subject; the respectable newspapers and reviews taking up the cudgels as strongly in my favour, as the others have done against me. Some of the vagabonds take great credit to themselves (grant us patience!) for having made me popular by publishing my books in newspapers: as if there were no England, no Scotland, no Germany, no place but America in the whole world. A splendid satire upon this kind of trash has just occurred. A man came here yesterday, and demanded, not besought, but demanded, pecuniary assistance; and fairly bullied Mr. Q---- for money. When I came home, I dictated a letter to this effect -- that such applications reached me in vast numbers every day; that if I were a man of fortune, I could not render assistance to all who sought it; and that, depending on my own exertion for all the help I could give, I regretted to say I could afford him none. Upon this, my gentleman sits down and writes me that he is an itinerant bookseller; that he is the first man who sold my books in New York; that he is distressed in the city where I am revelling in luxury; that he thinks it rather strange that the man who wrote Nickleby should be utterly destitute of feeling; and that he would have me 'take care I don't repent it.' What do you think of that? -- as Mac would say. I thought it such a good commentary, that I dispatched the letter to the editor of the only English newspaper here, and told him he might print it if he liked.

"I will tell you what I should like, my dear friend, always supposing that your judgment concurs with mine; and that you would take the trouble to get such a document. I should like to have a short letter addressed to me, by the principal English authors who signed the international copyright petition, expressive of their sense that I have done my duty to the cause. I am sure I deserve it, but I don't wish it on that ground. It is because its publication in the best journals here would unquestionably do great good. As the gauntlet is down, let us go on. Clay has already sent a gentleman to me express from Washington (where I shall be on the 6th or 7th of next month) to declare his strong interest in the matter, his cordial approval of the 'manly' course I have held in reference to it, and his desire to stir in it if possible. I have lighted up such a blaze that a meeting of the foremost people on the other side (very respectfully and properly conducted in reference to me, personally, I am bound to say) was held in this town t'other night. And it would be a thousand pities if we did not strike as hard as we can, now that the iron is so hot.

"I have come at last, and it is time I did, to my life here, and intentions for the future. I can do nothing that I want to do, go nowhere where I want to go, and see nothing that I want to see. If I turn into the street, I am followed by a multitude. If I stay at home, the house becomes, with callers, like a fair. If I visit a public institution, with only one friend, the directors come down incontinently, waylay me in the yard, and address me in a long speech. I go to a party in the evening, and am so enclosed and hemmed about by people, stand where I will, that I am exhausted for want of air. I dine out, and have to talk about everything and everybody. I go to church for quiet, and there is a violent rush to the neighbourhood of the pew I sit in. and the Clergyman preaches at me. I take my seat in a railroad car, and the very conductor won't leave me alone. I get out at a Station, and can't drink a glass of water, without having a hundred people looking down my throat when I open my mouth to swallow. Conceive what all this is! Then by every post, letters on letters arrive, all about nothing, and all demanding an immediate answer. This man is offended because I won't live in his house; and that man is thoroughly disgusted because I won't go out more than four times in one evening. I have no rest or peace, and am in a perpetual worry.

"Under these febrile circumstances, which this climate especially favours, I have come to the resolution that I will not (so far as my will has anything to do with the matter) accept any more public entertainments or public recognitions of any kind, during my stay in the United States; and in pursuance of this determination I have refused invitations from Philadelphia Baltimore, Washington, Virginia, Albany, and Providence. Heaven knows whether this will be effectual, but I shall soon see, for on Monday morning the 28th we leave for Philadelphia. There I shall only stay three days. Thence we go to Baltimore, and there I shall only stay three days. Thence to Washington, where we may stay perhaps ten days; perhaps not so long. Thence to Virginia, where we may halt for one day; and thence to Charleston, where we may pass a week perhaps; and where we shall very likely remain until your March letters reach us, through David Colden. I had a design of going from Charleston to Columbia in South Carolina, and there engaging a carriage, a baggage-tender and negro boy to guard the same, and a saddle-horse for myself -- with which caravan I intended going right away; as they say here, into the West, through the wilds of Kentucky and Tennessee, across the Alleghany Mountains, and so on until we should strike the lakes and could get to Canada. But it has been represented to me that this is a track only known to travelling merchants; that the roads are bad, the Country a tremendous waste, the inns log-houses, and the journey one that would play the very devil with Kate. I am staggered, but not deterred. If I find it possible to be done in the time, I mean to do it; being quite satisfied that without some such dash, I can never be a free agent, or see anything worth the telling.

"We mean to return home in a packet-ship -- not a steamer. Her name is the George Washington, and she will sail from here, for Liverpool, on the seventh of June. At that season of the year, they are seldom more than three weeks making the voyage; and I never will trust myself upon the wide ocean, if it please Heaven, in a steamer again. When I tell you all that I observed on board that Britannia, I shall astonish you. Meanwhile, consider two of their dangers. First, that if the funnel were blown overboard, the vessel must instantly be on fire, from stem to stern: to comprehend which Consequence, you have only to understand that the funnel is more than 40 feet high, and that at night you see the solid fire two or three feet above its top. Imagine this swept down by a strong wind, and picture to yourself the amount of flame on deck; and that a strong wind is likely to sweep it down you soon learn, from the precautions taken to keep it up in a storm, when it is the first thing thought of. Secondly, each of these boats consumes between London and Halifax 700 tons of coals and it is pretty clear, from this enormous difference of weight in a ship of only 1,200 tons burden in all, that she must be either too heavy when she comes out of port, or too light when she goes in. The daily difference in her rolling, as she burns the coals out, is something absolutely fearful. Add to all this, that by day and night she is full of fire and people, that she has no boats, and that the struggling of that enormous machinery in a heavy sea seems as though it would rend her into fragments -- and you may have a pretty considerable damned good sort of a feeble notion that it don't fit nohow; and that it an't calculated to make you smart, overmuch; and that you don't feel special bright; and by no means first-rate; and not at all tonguey (or disposed for conversation); and that however rowdy you may be by natur', it does use you up com-plete, and that's a fact; and makes you quake considerable, and disposed toe damn the engine! -- All of which phrases, I beg to add, are pure Americanisms of the first water.

"When we reach Baltimore, we are in the regions of slavery. It exists there, in its least shocking and most mitigated form but there it is. They whisper, here (they dare only whisper, you know, and that below their breaths), that on that place, and all through the South, there is a dull gloomy cloud on which the very word seems written. I shall be able to say, one of these days, that I accepted no public mark of respect in any place where slavery was; -- and that's something.

"The ladies of America are decidedly and unquestionably beautiful. Their complexions are not so good as those of Englishwomen; their beauty does not last so long; and their figures are very inferior. But they are most beautiful. I still reserve my opinion of the national character -- just whispering that I tremble for a Radical Coming here, unless he is a Radical on principle, by reason and reflection, and from the sense of right. I fear that if he were anything else, he would return home a Tory. . . . I say no more on that head for two months from this time, save that I do fear that the heaviest blow ever dealt at liberty will be dealt by this Country, in the failure of its example to the earth. The scenes that are passing in Congress now, all tending to the separation of the States, fill one with such a deep disgust that I dislike the very name of Washington (meaning the place, not the man), and am repelled by the mere thought of approaching it.

"Twenty-seventh February. Sunday.

"There begins to be great consternation here. in reference to the Cunard packet which (we suppose) left Liverpool on the fourth. She has not yet arrived. We scarcely know what to do with ourselves in our extreme anxiety to get letters from home. I have really had serious thoughts of going back to Boston, alone, to be nearer news. We have determined to remain here until Tuesday afternoon, if she should not arrive before, and to send Mr. Q---- and the luggage on to Philadelphia to-morrow morning. God grant she may not have gone down: but every ship that comes in brings intelligence of a terrible gale (which indeed was felt ashore here) on the night of the fourteenth; and the sea-captains swear (not without some prejudice, of course) that no steamer could have lived through it, supposing her to have been in its full fury. As there is no steam packet to go to England, supposing the Caledonia not to arrive, we are obliged to send our letters by the Garrick ship, which sails early tomorrow morning. Consequently I must huddle this up, and dispatch it to the post-office with all speed. I have so much to say that I could fill quires of paper, which renders this sudden pull-up the more provoking.

"I have in my portmanteau a petition for an international copyright law, signed by all the best American writers with Washington Irving at their head. They have requested me to hand it to Clay for presentation, and to back it with any remarks I may think proper to offer. So 'Hoo-roar for the principle, as the moneylender said, ven he vouldn't renoo the bill.'

God bless you. . . . You know what I would say about home and the darlings. A hundred times God bless you. . . . Fears are entertained for Lord Ashburton also. Nothing has been heard of him."

A brief letter, sent me next day by the minister's bag, was in effect a postscript to the foregoing; and expressed still more strongly the apprehensions his voyage out had impressed him with, and which, though he afterwards saw reason greatly to modify them, were not so strange at that time as they appear to us now.

"Canton House, New York, February twenty-eighth, 1842. . . . The Caledonia, I grieve and regret to say, has not arrived. If she left England to her time, she has been four and twenty days at sea. There is no news of her; and on the nights of the fourteenth and eighteenth it blew a terrible gale, which almost justifies the worst suspicions. For myself, I have hardly any hope of her; having seen enough, in our passage out, to Convince me that steaming across the ocean in heavy weather is as yet an experiment of the utmost hazard.

"As it was supposed that there would be no steamer whatever for England this month (since in ordinary course the Caledonia would have returned with the mails on 2 March) I hastily got the letters ready yesterday and sent them by the Garrick; which may perhaps be three weeks out, but is not very likely to be longer. But belonging to the Cunard Company is a boat called the Unicorn, which in the summer time plies up the St. Lawrence, and brings passengers from Canada to join the British and North American steamers at Halifax. In the winter she lies at the last-mentioned place; from which news has come this morning that they have sent her on to Boston for the mails; and, rather than interrupt the Communication, mean to dispatch her to England in lieu of the poor Caledonia. This in itself, by the way, is a daring deed; for she was originally built to run between Liverpool and Glasgow, and is no more designed for the Atlantic than a Calais packet-boat; though she once crossed it. in the summer season.

"You may judge, therefore, what the owners think of the probability of the Caledonia's arrival. How slight an alteration in our plans would have made us passengers on board of her!

"It would be difficult to tell you, my dear fellow, what an impression this has made upon our minds, or with what intense anxiety and suspense we have been waiting for your letters from home. We were to have gone South to-day, but linger here until to-morrow afternoon (having sent the secretary and luggage forward) for one more chance of news. Love to dear Macready, and to dear Mac, and every one we care for. It's useless to speak of the dear children. It seems now as though we should never hear of them. . . .

"P.S. Washington Irving is a great fellow. We have laughed most heartily together. He is just the man he ought to be. So is Doctor Channing, with whom I have had an interesting correspondence since I saw him last at Boston. Halleck is a merry little man. Bryant a sad one, and very reserved. Washington Allston the painter (who wrote Monaldi) is a fine specimen of a glorious old genius. Longfellow, whose volume of poems I have got for you, is a frank accomplished man as well as a fine writer, and will be in town 'next fall.' Tell Macready that I suspect prices here must have rather altered since his time. I paid our fortnight's bill here, last night. We have dined out every day (except when I was laid up with a sore throat), and only had in all four bottles of wine. The hill was £70 English!!!

"You will see, by my other letter, how we have been feted and feasted; and how there is war to the knife about the international Copyright; and how I will speak about it, and decline to be put down.

"Oh for news from home! I think of your letters so full of heart and friendship, with perhaps a little scrawl of Charley's or Mamey's, lying at the bottom of the deep sea; and am as full of sorrow as if they had once been living creatures. -- Well! they may come, yet."

They did reach him, but not by the Caledonia. His fears as to that vessel were but too well founded. On the very day when she was due in Boston (18 February) it was learnt in London that she had undergone misadventure; that, her decks having been swept and her rudder torn away, though happily no lives were lost, she had returned disabled to Cork; and that the Arcadia, having received her passengers and mails, was to sail with them from Liverpool next day.

Of the main subject of that letter written on the day preceding; of the quite unpremeditated impulse, out of which sprang his advocacy of claims which he felt to be represented in his person; of the injustice done by his entertainers to their guest in ascribing such advocacy to selfishness; and of the graver wrong done by them to their own highest interests, nay, even to their commonest and most vulgar interests, in Continuing to reject those claims; I will add nothing now to what all those years ago I laboured very hard to lay before many readers. It will be enough if I here print, from the author's letters I sent out to him by the next following mail in compliance with his wish, this which follows from a very dear friend of his and mine. I fortunately had it transcribed before I posted it to him; Mr. Carlyle having in some haste written from "Templand, 26 March, 1842," and taken no copy.

"We learn by the newspapers that you everywhere in America stir up the question of international copyright, and thereby awaken huge dissonance where all else were triumphant unison for you. I am asked my opinion of the matter, and requested to write it down in words.

"Several years ago, if memory err not, I was one of many English writers, who, under the auspices of Miss Martineau, did already sign a petition to congress praying for an international copyright between the two Nations, -- which properly are not two Nations, but one; indivisible by parliament, congress, or any kind of human law or diplomacy, being already united by Heaven's Act of Parliament, and the everlasting law of Nature and Fact. To that opinion I still adhere, and am like to continue adhering.

"In discussion of the matter before any congress or parliament manifold considerations and argumentations will necessarily arise; which to me are not interesting, nor essential for helping me to a decision. They respect the time and manner in which the thing should be; not at all whether the thing should be or not. In an ancient book, reverenced I should hope on both sides of the Ocean, it was thousands of years ago written down in the most decisive and explicit manner, 'Thou shalt not steal.' That thou belongest to a different 'Nation,' and canst steal without being certainly hanged for it, gives thee no permission to steal! Thou shalt not in anywise steal at all! So it is written down, for Nations and for Men, in the Law-Book of the Maker of this Universe. Nay, poor Jeremy Bentham and others step in here, and will demonstrate that it is actually our true convenience and expediency not to steal; which I for my share, on the great scale and on the small, and in all conceivable scales and shapes, do also firmly believe it to be. For example, if Nations abstained from stealing, what need were there of fighting, -- with its butcherings and burnings, decidedly the most expensive thing in this world? How much more two Nations, which, as I said, are but one Nation; knit in a thousand ways by Nature and Practical Intercourse; indivisible brother elements of the same great SAXONDOM, to which in all honourable ways be long life!

"When Mr. Robert Roy M'Gregor lived in the district of Menteith on the Highland border two centuries ago, he for his part found it more convenient to supply himself with beef by stealing it alive from the adjacent glens, than by buying it killed in the Stirling butchers'-market. It was Mr. Roy's plan of supplying himself with beef in those days, this of stealing it. In many a little 'Congress' in the district of Menteith, there was debating, doubt it not, and much specious argumentation this way and that, before they could ascertain that, really and truly, buying was the best way to get your beef; which however in the long run they did with one assent find it indisputably to be: and accordingly they hold by it to this day."

This brave letter was an important service rendered at a critical time, and Dickens was very grateful for it. But, as time went on, he had other and higher causes for gratitude to its writer. Admiration of Carlyle increased with his years; and there was no one whom in later life he honoured so much, or had a more profound regard for.

IV

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTH

1842

Dickens's next letter was begun in the "United-states-hotel, Philadelphia," and bore date "Sunday, sixth March, 1842." It treated of much dealt with afterwards at greater length in the Notes, but the freshness and vivacity of the first impressions in it have surprised me. I do not however print any passage here which has not its own interest independently of anything contained in that book. The rule will be continued, as in the portions of letters already given, of not transcribing anything before printed, or anything having even but a near resemblance to descriptions that appear in the Notes.

". . . As this is likely to be the only quiet day I shall have for a long time, I devote it to writing to you. We have heard nothing from you yet, and only have for our consolation the reflection that the Columbia is now on her way out. No news had been heard of the Caledonia yesterday afternoon, when we left New York. We were to have quitted that place last Tuesday, but have been detained there all the week by Kate having so bad a sore throat that she was obliged to keep her bed. We left yesterday afternoon at five o'clock, and arrived here at eleven last night. Let me say, by the way, that this is a very trying climate.

"I have often asked Americans in London which were the better railroads -- ours or theirs? They have taken time for reflection, and generally replied, on mature consideration, that they rather thought we excelled; in respect of the punctuality with which we arrived at our stations, and the smoothness of our travelling. I wish you could see what an American railroad is, in some parts where I now have seen them. I won't say I wish you could feel what it is, because that would be an unchristian and savage aspiration. It is never inclosed, or warded off. You walk down the main street of a large town: and, slap-dash, headlong, pell-mell, down the middle of the street; with pigs burrowing, and boys flying kites and playing marbles, and men smoking, and women talking, and children crawling, close to the very rails; there comes tearing along a mad locomotive with its train of cars, scattering a red-hot shower of sparks (from its wood fire) in all directions; screeching, hissing, yelling, and painting; and nobody one atom more concerned than if it were a hundred miles away. You cross a turnpike-road; and there is no gate, no policeman, no signal -- nothing to keep the wayfarer or quiet traveller out of the way, but a wooden arch on which is written in great letters 'Look out for the locomotive.' And if any man, woman, or child, don't look out, why it's his or her fault, and there's an end of it.

"The cars are like very shabby omnibuses -- only larger; holding sixty or seventy people. The seats, instead of being placed long ways, are put cross-wise, back to front. Each holds two. There is a long row of these on each side of the caravan, and a narrow passage up the centre. The windows are usually all closed, and there is very often, in addition, a hot, close, most intolerable charcoal stove in a red-hot glow. The heat and closeness are quite insupportable. But this is the characteristic of all American houses, of all the public institutions, chapels, theatres, and prisons. From the constant use of the hard anthracite coal in these beastly furnaces, a perfectly new class of diseases is springing up in the country. Their effect upon an Englishman is briefly told. He is always very sick and very faint; and has an intolerable headache, morning, noon, and night.

"In the ladies' car, there is no smoking of tobacco allowed. All gentlemen who have ladies with them, sit in this car; and it is usually very full. Before it, is the gentlemen's car; which is something narrower. As I had a window close to me yesterday which commanded this gentlemen's car, I looked at it pretty often, perforce. The flashes of saliva flew so perpetually and incessantly out of the windows all the way, that it looked as though they were ripping open feather-beds inside, and letting the wind dispose of the feathers. But this spitting is universal. In the courts of law, the judge has his spittoon on the bench, the counsel have theirs, the witness has his, the prisoner his, and the crier his. The jury are accommodated at the rate of three men to a spittoon (or spit-box as they call it here); and the spectators in the gallery are provided for, as so many men who in the course of nature expectorate without cessation. There are spit-boxes in every steamboat, bar-room, public dining-room, house of office, and place of general resort, no matter what it be. In the hospitals, the students are requested, by placard, to use the boxes provided for them, and not to spit upon the stairs. I have twice seen gentlemen, at evening parties in New York, turn aside when they were not engaged in conversation, and spit upon the drawing-room carpet. And in every bar-room and hotel passage the stone floor looks as if it were paved with open oysters -- from the quantity of this kind of deposit which tesselates it all over. . . .

"The institutions at Boston, and at Hartford, are most admirable. It would be very difficult indeed to improve upon them. But this is not so at New York; where there is an ill-managed lunatic asylum, a bad jail, a dismal workhouse, and a perfectly intolerable place of police-imprisonment. A man is found drunk in the streets, and is thrown into a cell below the surface of the earth; profoundly dark; so full of noisome vapours that when you enter it with a candle you see a ring about the light, like that which surrounds the moon in wet and cloudy weather; and so offensive and disgusting in its filthy odours, that you cannot bear its stench. He is shut up within an iron door, in a series of vaulted passages where no one stays; has no drop of water, or ray of light, or visitor, or help of any kind; and there he remains until the magistrate's arrival. If he die (as one man did not long ago) he is half eaten by the rats in an hour's time (as this man was). I expressed, on seeing these places the other night, the disgust I felt, and which it would be impossible to repress. 'Well; I don't know,' said the night constable -- that's a national answer by the bye -- 'Well; I don't know. I've had six and twenty young women locked up here together, and beautiful ones too, and that's a fact.' The cell was certainly no larger than the wine-cellar in Devonshire-terrace; at least three feet lower; and stunk like a common sewer. There was one woman in it, then. The magistrate begins his examinations at five o'clock in the morning; the watch is set at seven at night; if the prisoners have been given in charge by an officer, they are not taken out before nine or ten; and in the interval they remain in these places, where they could no more be heard to cry for help, in case of a fit or swoon among them, than a man's voice could be heard after he was coffined up in his grave.

"There is a prison in the same city, and indeed in the same building, where prisoners for grave offences await their trial, and to which they are sent back when under remand. It sometimes happens that a man or woman will remain here for twelve months, waiting the result of motions for new trial, and in arrest of judgment, and what not. I went into it the other day: without any notice or preparation, otherwise I find it difficult to catch them in their work-a-day aspect. I stood in a long, high, narrow building, consisting of four galleries one above the other, with a bridge across each, on which sat a turnkey, sleeping or reading as the case might be. From the roof, a couple of wind-sails dangled and drooped, limp and useless; the skylight being fast closed, and they only designed for summer use. In the centre of the building was the eternal stove; and along both sides of every gallery was a long row of iron doors -- looking like furnace doors, being very small, but black and cold as if the fires within had gone out.

"A man with keys appears, to show us round. A good-looking fellow, and, in his way, civil and obliging." (I omit a dialogue of which the substance has been printed, and give only that which appears for the first time here.)

"'Suppose a man's here for twelve months. Do you mean to say he never comes out at that little iron door?'

"'He may walk some, perhaps -- not much.'

"'Will you show me a few of them?'

"'Ah! All, if you like.'

"He threw open a door, and I looked in. An old man was sitting on his bed, reading. The light came in through a small chink, very high up in the wall. Across the room ran a thick iron pipe to carry off filth; this was bored for the reception of something like a big funnel in shape; and over the funnel was a water-cock. This was his washing apparatus and water-closet. It was not savoury, but not very offensive. He looked up at me; gave himself an odd, dogged kind of shake; and fixed his eyes on his book again. I came out, and the door was shut and locked. He had been there a month, and would have to wait another month for his trial. 'Has he ever walked out now, for instance?' 'No. . . .'

"'In England, if a man is under sentence of death even, he has a yard to walk in at certain times.'

"'Possible?'

"Making me this answer with a coolness which is perfectly untranslateable and inexpressible, and which is quite peculiar to the soil, he took me to the women's side; telling me, upon the way, all about this man, who, it seems, murdered his wife, and will certainly be hanged. The women's doors have a small square aperture in them; I looked through one, and saw a pretty boy about ten or twelve years old, who seemed lonely and miserable enough -- as well he might. 'What's he been doing?' says I. 'Nothing,' says my friend. 'Nothing!' says I. 'No,' says he. 'He's here for safe keeping. He saw his father kill his mother, and is detained to give evidence against him -- that was his father you saw just now.' 'But that's rather hard treatment for a witness, isn't it?' -- 'Well! I don't know. It an't a very rowdy life, and that's a fact.' So my friend, who was an excellent fellow in his way, and very obliging, and a handsome young man to boot, took me off to show me some more curiosities; and I was very much obliged to him, for the place was so hot, and I so giddy, that I could scarcely stand. . . .

"When a man is hanged in New York, he is walked out of one of these cells, without any condemned sermon or other religious formalities, straight into the narrow jail yard, which may be about the width of Cranbourn-alley. There, a gibbet is erected, which is of curious construction; for the culprit stands on the earth with the rope about his neck, which passes through a pulley in the top of the 'Tree' (see Newgate Calendar passim), and is attached to a weight something heavier than the man. This weight, being suddenly let go, drags the rope down with it, and sends the criminal flying up fourteen feet into the air; while the judge, and jury, and five and twenty citizens (whose presence is required by the law), stand by, that they may afterwards certify to the fact. This yard is a very dismal place; and when I looked at it, I thought the practice infinitely superior to ours; much more solemn, and far less degrading and indecent.

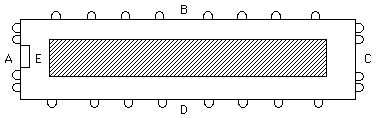

"There is another prison near New York which is a house of correction. The convicts labour in stone quarries near at hand, but the jail has no covered yards or shops, so that when the weather is wet (as it was when I was there) each man is shut up in his own little cell, all the live-long day. These cells, in all the correction-houses I have seen, are on one uniform plan -- thus:

A, B, C, and D, are the walls of the building with windows in them, high up in the wall. The shaded place in the centre represents four tiers of cells, one above the other, with doors of grated iron, and a light grated gallery to each tier. Four tiers front to B, and four to D, so that by this means you may be said, in walking round, to see eight tiers in all. The intermediate blank space you walk in, looking up at these galleries; so that, coming in at the door E, and going either to the right or left till you come back to the door again, you see all the cells under one roof and in one high room. Imagine them in number 400, and in every one a man locked up; this one with his hands through the bars of his grate, this one in bed (in the middle of the day, remember), and this one flung down in a heap upon the ground with his head against the bars like a wild beast. Make the rain pour down in torrents outside. Put the everlasting stove in the midst; hot, suffocating, and vaporous, as a witch's cauldron. Add a smell like that of a thousand old mildewed umbrellas wet through, and a thousand dirty clothes-bags musty, moist, and fusty, and you will have some idea -- a very feeble one, my dear friend, on my word -- of this place yesterday week. You know of course that we adopted our improvements in prison-discipline from the American pattern; but I am confident that the writers who have the most lustily lauded the American prisons, have never seen Chesterton's domain or Tracey's. There is no more comparison between those two prisons of ours, and any I have seen here Yet, than there is between the keepers here, and those two gentlemen. Putting out of sight the difficulty we have in England of finding useful labour for the prisoners (which of course arises from our being an older country, and having vast numbers of artizans unemployed), our system is more complete, more impressive, and more satisfactory in every respect. It is very possible that I have not come to the best, not having yet seen Mount Auburn. I will tell you when I have. And also when I have come to those inns, mentioned -- vaguely rather -- by Miss Martineau, where they undercharge literary people for the love the landlords bear them. My experience, so far, has been of establishments where (perhaps for the same reason) they very monstrously and violently overcharge a man whose position forbids remonstrance.

"Washington, Sunday, March the Thirteenth, 1842.

"In allusion to the last sentence, my dear friend, I must tell you a slight experience I had in Philadelphia. My rooms had been ordered for a week, but, in consequence of Kate's illness, only Mr. Q---- and the luggage had gone on. Mr. Q---- always lives at the table d'hôte, so that while we were in New York our rooms were empty. The landlord not only charged me half the full rent for the time during which the rooms were reserved for us (which was quite right), but charged me also for board for myself and Kate and Anne, at the rate of nine dollars per day for the same period, when we were actually living, at the same expense, in New York!!! I did remonstrate upon this head; but was coolly told it was the custom (which I have since been assured is a lie), and had nothing for it but to pay the amount. What else could I do? I was going away by the steamboat at five o'clock in the morning; and the landlord knew perfectly well that my disputing an item of his bill would draw down upon me the sacred wrath of the newspapers, which would one and all demand in capitals if This was the gratitude of the man whom America had received as she had never received any other man but La Fayette?

"I went last Tuesday to the Eastern Penitentiary near Philadelphia, which is the only prison in the States, or I believe, in the world, on the principle of hopeless, strict, and unrelaxed solitary confinement, during the whole term of the sentence. It is wonderfully kept, but a most dreadful, fearful place. The inspectors, immediately on my arrival in Philadelphia, invited me to pass the day in the jail, and to dine with them when I had finished my inspection, that they might hear my opinion of the system. Accordingly I passed the whole day in going from cell to cell, and conversing with the prisoners. Every facility was given me, and no constraint whatever imposed upon any man's free speech. If I were to write you a letter of twenty sheets, I could not tell you this one day's work; so I will reserve it until that happy time when we shall sit round the table at Jack Straw's -- you, and I, and Mac -- and go over my diary. I never shall be able to dismiss from my mind the impressions of that day. Making notes of them, as I have done, is an absurdity, for they are written, beyond all power of erasure, in my brain. I saw men who had been there, five years, six years, eleven years, two years, two months, two days; some whose term was nearly over, and some whose term had only just begun. Women too, under the same variety of circumstances. Every prisoner who comes into the jail, comes at night; is put into a bath, and dressed in the prison garb; and then a black hood is drawn over his face and head, and he is led to the cell from which he never stirs again until his whole period of confinement has expired. I looked at some of them with the same awe as I should have looked at men who had been buried alive, and dug up again.

"We dined in the jail: and I told them after dinner how much the sight had affected me, and what an awful punishment it was. I dwelt upon this; for, although the inspectors are extremely kind and benevolent men, I question whether they are sufficiently acquainted with the human mind to know what it is they are doing. Indeed, I am sure they do not know. I bore testimony, as every one who sees it must, to the admirable government of the institution (Stanfield is the keeper: grown a little younger, that's all); and added that nothing could justify such a punishment, but its working a reformation in the prisoners. That for short terms -- say two years for the maximum -- I conceived, especially after what they had told me of its good effects in certain cases, it might perhaps be highly beneficial; but that, carried to so great an extent, I thought it cruel and unjustifiable; and further, that their sentences for small offences were very rigorous, not to say savage. All this, they took like men who were really anxious to have one's free opinion, and to do right. And we were very much pleased with each other, and parted in the friendliest way.

"They sent me back to Philadelphia in a carriage they had sent for me in the morning; and then I had to dress in a hurry, and follow Kate to Cary's the bookseller's where there was a party. He married a sister of Leslie's. There are three Miss Leslies here, very accomplished; and one of them has copied all her brother's principal pictures. These copies hang about the room. We got away from this as soon as we could; and next morning had to turn out at five. In the morning I had received and shaken hands with five hundred people, so you may suppose that I was pretty well tired. Indeed I am obliged to be very careful of myself; to avoid smoking and drinking; to get to bed soon; and to be particular in respect of what I eat. . . . You cannot think how bilious and trying the climate is. One day it is hot summer, without a breath of air; the next, twenty degrees below freezing, with a wind blowing that cuts your skin like steel. These changes have occurred here several times since last Wednesday night.

"I have altered my route, and don't mean to go to Charleston. The country, all the way from here, is nothing but a dismal swamp; there is a bad night of sea-coasting in the journey; the equinoctial gales are blowing hard; and Clay (a most charming fellow, by the bye), whom I have consulted, strongly dissuades me. The weather is intensely hot there; the spring fever is coming on; and there is very little to see, after all. We therefore go next Wednesday night to Richmond, which we shall reach on Thursday. There, we shall stop three days; my object being to see some tobacco plantations. Then we shall go by James river back to Baltimore, which we have already passed through, and where we shall stay two days. Then we shall go West at once, straight through the most gigantic part of this continent: across the Alleghany-mountains, and over a prairie.

"STILL AT WASHINGTON, Fifteenth March, 1842. . . . It is impossible, my dear friend, to tell you what we felt, when Mr. Q---- (who is a fearfully sentimental genius, but heartily interested in all that concerns us) came to where we were dining last Sunday, and sent in a note to the effect that the Caledonia had arrived! Being really assured of her safety, we felt as if the distance between us and home were diminished by at least one half. There was great joy everywhere here, for she had been quite despaired of, but our joy was beyond all telling. This news came on by express. Last night your letters reached us. I was dining with a club (for I can't avoid a dinner of that sort, now and then), and Kate sent me a note about nine o'clock to say they were here. But she didn't open them -- which I consider heroic -- until I came home. That was about half-past ten; and we read them until nearly two in the morning.

"I won't say a word about your letters; except that Kate and I have come to a conclusion which makes me tremble in my shoes, for we decide that humorous narrative is your forte, and not statesmen of the commonwealth. I won't say a word about your news; for how could I in that case, while you want to hear what we are doing, resist the temptation of expending pages on those darling children. . . .

"I have the privilege of appearing on the floor of both houses here, and go to them every day. They are very handsome and commodious. There is a great deal of bad speaking, but there are a great many very remarkable men, in the legislature: such as John Quincey Adams, Clay, Preston, Calhoun, and others: with whom I need scarcely add I have been placed in the friendliest relations. Adams is a fine old fellow -- seventy-six years old, but with most surprising vigour, memory, readiness, and pluck. Clay is perfectly enchanting; an irresistible man. There are some very noble specimens, too, out of the West. Splendid men to look at, hard to deceive, prompt to act, lions in energy, Crichtons in varied accomplishments, Indians in quickness of eye and gesture, Americans in affectionate and generous impulse. It would be difficult to exaggerate the nobility of some of these glorious fellows.

"When Clay retires, as he does this month, Preston will become the leader of the whig party. He so solemnly assures me that the international copyright shall and will be passed, that I almost begin to hope; and I shall be entitled to say, if it be, that I have brought it about. You have no idea how universal the discussion of its merits and demerits has become; or how eager for the change I have made a portion of the people.

"You remember what Webster was, in England. If you could but see him here! If you could only have seen him when he called on us the other day -- feigning abstraction in the dreadful pressure of affairs of state; rubbing his forehead as one who was a-weary of the world; and exhibiting a sublime caricature of Lord Burleigh. He is the only thoroughly unreal man I have seen on this side of the ocean. Heaven help the President! All parties are against him, and he appears truly wretched. We go to a levee at his house to-night. He has invited me to dinner on Friday, but I am obliged to decline; for we leave, per steamboat, to-morrow night.

"I said I wouldn't write anything more concerning the American people, for two months. Second thoughts are best. I shall not change, and may as well speak out -- to you. They are friendly, earnest, hospitable, kind, frank, very often accomplished, far less prejudiced than you would suppose, warm-hearted, fervent, and enthusiastic. They are chivalrous in their universal politeness to women, courteous, obliging, disinterested; and, when they conceive a perfect affection for a man (as I may venture to say of myself), entirely devoted to him. I have received thousands of people of all ranks and grades, and have never once been asked an offensive or unpolite question -- except by Englishmen, who, when they have been 'located' here for some years, are worse than the devil in his blackest painting. The State is a parent to its people; has a parental care and watch over all poor children, women labouring of child, sick persons, and captives. The common men render you assistance in the streets, and would revolt from the offer of a piece of money. The desire to oblige is universal; and I have never once travelled in a public conveyance, without making some generous acquaintance whom I have been sorry to part from, and who has in many cases come on miles, to see us again. But I don't like the country. I would not live here on any consideration. It goes against the grain with me. It would with you. I think it impossible, utterly impossible, for any Englishman to live here, and be happy. I have a confidence that I must be right, because I have everything, God knows, to lead me to the opposite conclusion: and yet I cannot resist coming to this one. As to the causes, they are too many to enter upon here. . . .

"One of two petitions for an international copyright which I brought here from American authors, with Irving at their head, has been presented to the house of representatives. Clay retains the other for presentation to the senate after I have left Washington. The presented one has been referred to a committee; the Speaker has nominated as its chairman Mr. Kennedy, member for Baltimore, who is himself an author and notoriously favourable to such a law; and I am going to assist him in his report.

"RICHMOND, IN VIRGINIA. Thursday Night, March 17.

"Irving was with me at Washington yesterday, and wept heartily at parting. He is a fine fellow, when you know him well; and you would relish him, my dear friend, of all things. We have laughed together at some absurdities we have encountered in company, quite in my vociferous Devonshire-terrace style. The 'Merrikin' government have treated him, he says, most liberally and handsomely in every respect. He thinks of sailing for Liverpool on 7 April; passing a short time in London; and then going to Paris. Perhaps you may meet him. If you do, he will know that you are my dearest friend, and will open his whole heart to you at once. His secretary of legation, Mr. Coggleswell, is a man of very remarkable information, a great traveller, a good talker, and a scholar.

"I am going to sketch you our trip here from Washington, as it involves nine miles of a 'Virginny Road.' That done, I must be brief, good brother. . . ."

The reader of the American Notes will remember the humorous descriptions of the night steamer on the Potomac, and of the black driver over the Virginia Road. Both were in this letter; which, after three days, he resumed "At Washington again, Monday, March the twenty-first.

We had intended to go to Baltimore from Richmond, by a place called Norfolk: but one of the boats being under repair, I found we should probably be detained at this Norfolk two days. Therefore we came back here yesterday, by the road we had travelled before; lay here last night; and go on to Baltimore this afternoon, at four o'clock. It is a journey of only two hours and a half. Richmond is a prettily situated town; but, like other towns in slave districts (as the planters themselves admit), has an aspect of decay and gloom which to an unaccustomed eye is most distressing. In the black car (for they don't let them sit with the whites) on the railroad as we went there, were a mother and family whom the steamer was Conveying away, to sell; retaining the man (the husband and father I mean) on his plantation. The children cried the whole way. Yesterday, on board the boat, a slave owner and two constables were our fellow-passengers. They were Coming here in search of two negroes who had run away on the previous day. On the bridge at Richmond there is a notice against fast driving over it, as it is rotten and crazy: penalty -- for whites, five dollars; for slaves, fifteen stripes. My heart is lightened as if a great load had been taken from it, when I think that we are turning our backs on this accursed and detested system. I really don't think I could have borne it any longer. It is all very well to say 'be silent on the subject.' They won't let you be silent. They will ask you what you think of it; and will expatiate on slavery as if it were one of the greatest blessings of mankind. 'It's not,' said a hard, bad-looking fellow to me the other day, 'it's not the interest of a man to use his slaves ill. It's damned nonsense that you hear in England.' -- I told him quietly that it was not a man's interest to get drunk, or to steal, or to game, or to indulge in any other vice, but he did indulge in it for all that. That cruelty, and the abuse of irresponsible power, were two of the bad passions of human nature, with the gratification of which, considerations of interest or of ruin had nothing whatever to do; and that, while every candid man must admit that even a slave might be happy enough with a good master, all human beings knew that bad masters, cruel masters, and masters who disgraced the form they bore, were matters of experience and history, whose existence was as undisputed as that of slaves themselves. He was a little taken aback by this, and asked me if I believed in the Bible. Yes, I said, but if any man could prove to me that it sanctioned slavery, I would place no further credence in it. 'Well, then,' he said, 'by God, sir, the niggers must be kept down, and the whites have put down the coloured people wherever they have found them.' 'That's the whole question,' said I. 'Yes, and by God,' says he, 'the British had better not stand out on that point when Lord Ashburton comes over, for I never felt so warlike as I do now, -- and that's a fact.' I was obliged to accept a public supper in this Richmond, and I saw plainly enough, there, that the hatred which these Southern States bear to us as a nation has been fanned up and revived again by this Creole business, and can scarcely be exaggerated. . . . We were desperately tired at Richmond, as we went to a great many places, and received a very great number of visitors. We appoint usually two hours in every day for this latter purpose, and have our room so full at that period that it is difficult to move or breathe. Before we left Richmond, a gentleman told me, when I really was so exhausted that I could hardly stand, that 'three people of great fashion' were much offended by having been told, when they called last evening, that I was tired and not visible, then, but would be 'at home' from twelve to two next day! Another gentleman (no doubt of great fashion also) sent a letter to me two hours after I had gone to bed preparatory to rising at four next morning, with instructions to the slave who brought it to knock me up and wait for an answer!

"I am going to break my resolution of accepting no more public entertainments, in favour of the originators of the printed document overleaf. They live upon the confines of the Indian territory, some two thousand miles or more west of New York! Think of my dining there! And yet, please God, the festival will come off -- I should say about the 12th or 15th of next month. . . ."

The printed document was a series of resolutions, moved at a public meeting attended by all the principal citizens, judges, professors, and doctors of St. Louis, urgently inviting, to that city of the Far West, the distinguished writer, then the guest of America, eulogising his genius, and tendering to him their warmest hospitalities. He was at Baltimore when he closed his letter.

"BALTIMORE. Tuesday, March 22nd.

"I have a great diffidence in running counter to any impression formed by a man of Maclise's genius, on a subject he has fully considered." (Referring apparently to some remark by myself on the picture of the Play-scene in Hamlet exhibited this year.) "But I quite agree with you about the King in Hamlet. Talking of Hamlet, I constantly carry in my greatcoat pocket the Shakespeare you bought for me in Liverpool. What an unspeakable source of delight that book is to me!

"Your Ontario letter I found here to-night: sent on by the vigilant and faithful Colden, who makes everything having reference to us, or our affairs, a labour of the heartiest love. We devoured its contents, greedily. Good Heaven, my dear fellow, how I miss you! and how I count the time 'twixt this and coming home again. Shall I ever forget the day of our parting at Liverpool! when even ---- became jolly and radiant in his sympathy with our separation! Never, never shall I forget that time. Ah! how seriously I thought then, and how seriously I have thought many, many times since, of the terrible folly of ever quarrelling with a true friend, on good for nothing trifles! Every little hasty word that has ever passed between us rose up before me like a reproachful ghost. At this great distance, I seem to look back upon any miserable small interruption of our affectionate intercourse, though only for the instant it has never outlived, with a sort of pity for myself as if I were another creature.

"I have bought another accordion. The steward lent me one, on the passage out, and I regaled the ladies' cabin with my performances. You can't think with what feeling I play Home Sweet Home every night, or how pleasantly sad it makes us. . . . And so God bless you. . . . I leave space for a short postscript before sealing this, but it will probably contain nothing. The dear, dear children! what a happiness it is to know that they are in such hands.

"P.S. Twenty-third March, 1842. Nothing new. And all well. I have not heard that the Columbia is in, but she is hourly expected. Washington Irving has come on for another leave-taking, and dines with me to-day. We start for the West, at half after eight to-morrow morning. I send you a newspaper, the most respectable in the States, with a very just copyright article."

V

CANAL AND STEAM BOAT JOURNEYS

1842

It would not be possible that a more vivid or exact impression, than that which is derivable from these letters, could be given of either the genius or the character of the writer. The whole man is here in the supreme hour of his life, and in all the enjoyment of its highest sensations. Inexpressibly sad to me has been the task of going over them, but the surprise has equalled the sadness. I had forgotten what was in them. That they contained, in their first vividness, all the most prominent descriptions of his published book, I knew. But the reproduction of any part of these was not permissible here; and believing that the substance of them had been thus almost wholly embodied in the American Notes, when they were lent to assist in its composition, I turned to them with very small expectation of finding anything available for present use. Yet the difficulty has been, not to find but to reject; and the rejection when most unavoidable has not been most easy. Even where the subjects recur that are in the printed volume, there is a freshness of first impressions in the letters that renders it no small trial to act strictly on the rule adhered to in these extracts from them. In the Notes there is of course very much, masterly in observation and description, of which there is elsewhere no trace; but the passages amplified from the letters have not been improved, and the manly force and directness of some of their views and reflections, conveyed by touches of a picturesque completeness that no elaboration could give, have here and there not been strengthened by rhetorical additions in the printed work. There is also a charm in the letters which the plan adopted in the book necessarily excluded from it. It will always of course have value as a deliberate expression of the results gathered from the American experiences, but the personal narrative of this famous visit to America is in the letters alone. In what way his experiences arose, the desire at the outset to see nothing that was not favourable, the slowness with which adverse impressions were formed, and the eager recognition of every better quality that arose and remained above the fault-finding, are discoverable only in the letters.