The Pickwick PapersCHAPTER XXII: MR. PICKWICK JOURNEYS TO IPSWICH, AND MEETS WITH A ROMANTIC ADVENTURE WITH A MIDDLE-AGED LADY IN YELLOW CURL PAPERS.

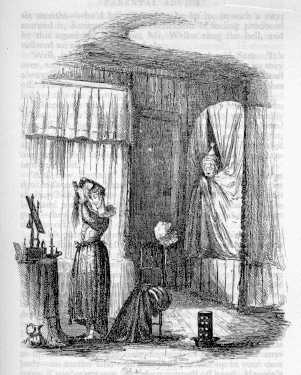

The more stairs Mr. Pickwick went down, the more stairs there seemed to be to descend, and again and again, when Mr. Pickwick got into some narrow passage, and began to congratulate himself on having gained the ground-floor, did another flight of stairs appear before his astonished eyes. At last he reached a stone hall, which he remembered to have seen when he entered the house. Passage after passage did he explore; room after room did he peep into; at length, as he was on the point of giving up the search in despair, he opened the door of the identical room in which he had spent the evening, and beheld his missing property on the table. Mr. Pickwick seized the watch in triumph, and proceeded to re-trace his steps to his bed-chamber. If his progress downward had been attended with difficulties and uncertainty, his journey back was infinitely more perplexing. Rows of doors, garnished with boots of every shape, make, and size, branched off in every possible direction. A dozen times did he softly turn the handle of some bed-room door which resembled his own, when a gruff cry from within of "Who the devil's that?" or "What do you want here?" caused him to steal away, on tiptoe, with a perfectly marvellous celerity. He was reduced to the verge of despair, when an open door attracted his attention. He peeped in. Right at last! There were the two beds, whose situation he perfectly remembered, and the fire still burning. His candle, not a long one when he first received it, had flickered away in the drafts of air through which he had passed, and sank into the socket as he closed the door after him. "No matter," said Mr. Pickwick, "I can undress myself just as well by the light of the fire." The bedsteads stood one on each side of the door; and on the inner side of each was a little path, terminating in a rush-bottomed chair, just wide enough to admit of a person's getting into, or out of bed, on that side, if he or she thought proper. Having carefully drawn the curtains of his bed on the outside, Mr. Pickwick sat down on the rush-bottomed chair and leisurely divested himself of his shoes and gaiters. He then took off and folded up his coat, waistcoat, and neckcloth, and slowly drawing on his tasselled night-cap, secured it firmly on his head, by tying beneath his chin the strings which he always had attached to that article of dress. It was at this moment that the absurdity of his recent bewilderment struck upon his mind. Throwing himself back in the rush-bottomed chair, Mr. Pickwick laughed to himself so heartily, that it would have been quite delightful to any man of well-constituted mind to have watched the smiles that expanded his amiable features as they shone forth from beneath the night-cap. "It is the best idea," said Mr. Pickwick to himself, smiling till he almost cracked the night-cap strings: "It is the best idea, my losing myself in this place, and wandering about those staircases, that I ever heard of. Droll, droll, very droll." Here Mr. Pickwick smiled again, a broader smile than before, and was about to continue the process of undressing, in the best possible humour, when he was suddenly stopped by a most unexpected interruption; to wit, the entrance into the room of some person with a candle, who, after locking the door, advanced to the dressing table, and set down the light upon it. The smile that played on Mr. Pickwick's features was instantaneously lost in a look of the most unbounded and wonder-stricken surprise. The person, whoever it was, had come in so suddenly and with so little noise, that Mr. Pickwick had had no time to call out, or oppose their entrance. Who could it be? A robber? Some evil-minded person who had seen him come up-stairs with a handsome watch in his hand, perhaps. What was he to do! The only way in which Mr. Pickwick could catch a glimpse of his mysterious visitor with the least danger of being seen himself, was by creeping on to the bed, and peeping out from between the curtains on the opposite side. To this manoeuvre he accordingly resorted. Keeping the curtains carefully closed with his hand, so that nothing more of him could be seen than his face and night-cap, and putting on his spectacles, he mustered up courage, and looked out. Mr. Pickwick almost fainted with horror and dismay. Standing before the dressing-glass was a middle-aged lady, in yellow curl-papers, busily engaged in brushing what ladies call their "back-hair." However the unconscious middle-aged lady came into that room, it was quite clear that she contemplated remaining there for the night; for she had brought a rushlight and shade with her, which, with praiseworthy precaution against fire, she had stationed in a basin on the floor, where it was glimmering away, like a gigantic lighthouse in a particularly small piece of water. "Bless my soul," thought Mr. Pickwick, "what a dreadful thing!" "Hem!" said the lady; and in went Mr. Pickwick's head with automaton-like rapidity. "I never met with anything so awful as this." thought poor Mr. Pickwick, the cold perspiration starting in drops upon his night-cap. "Never. This is fearful." It was quite impossible to resist the urgent desire to see what was going forward. So out went Mr. Pickwick's head again. The prospect was worse than before. The middle-aged lady had finished arranging her hair; had carefully enveloped it in a muslin night-cap with a small plaited border; and was gazing pensively on the fire. "This matter is growing alarming," reasoned Mr. Pickwick with himself. "I can't allow things to go on in this way. By the self-possession of that lady it is clear to me that I must have come into the wrong room. If I call out she'll alarm the house; but if I remain here the consequences will be still more frightful." Mr. Pickwick, it is quite unnecessary to say, was one of the most modest and delicate-minded of mortals. The very idea of exhibiting his night-cap to a lady overpowered him, but he had tied those confounded strings in a knot, and, do what he would, he couldn't get it off. The disclosure must be made. There was only one other way of doing it. He shrunk behind the curtains, and called out very loudly; "Ha - hum!" That the lady started at this unexpected sound was evident, by her falling up against the rushlight shade; that she persuaded herself it must have been the effect of imagination was equally clear, for when Mr. Pickwick, under the impression that she had fainted away stone-dead from fright, ventured to peep out again, she was gazing pensively on the fire as before. "Most extraordinary female this," thought Mr. Pickwick, popping in again. "Ha - hum!" These last sounds, so like those in which, as legends inform us, the ferocious giant Blunderbore was in the habit of expressing his opinion that it was time to lay the cloth, were too distinctly audible to be again mistaken for the workings of fancy. "Gracious Heaven!" said the middle-aged lady, "what's that?" "It's - it's - only a gentleman, Ma'am," said Mr. Pickwick from behind the curtains. "A gentleman!" said the lady with a terrific scream. "It's all over!" thought Mr. Pickwick. "A strange man!" shrieked the lady. Another instant and the house would be alarmed. Her garments rustled as she rushed towards the door. "Ma'am," said Mr. Pickwick, thrusting out his head, in the extremity of his desperation, "Ma'am!" Now, although Mr. Pickwick was not actuated by any definite object in putting out his head, it was instantaneously productive of a good effect. The lady, as we have already stated, was near the door. She must pass it, to reach the staircase, and she would most undoubtedly have done so by this time, had not the sudden apparition of Mr. Pickwick's night-cap driven her back into the remotest corner of the apartment, where she stood staring wildly at Mr. Pickwick, while Mr. Pickwick in his turn stared wildly at her. "Wretch," said the lady, covering her eyes with her hands, "what do you want here?" "Nothing, Ma'am; nothing, whatever, Ma'am;" said Mr. Pickwick earnestly. "Nothing!" said the lady, looking up. "Nothing, Ma'am, upon my honour," said Mr. Pickwick, nodding his head so energetically that the tassel of his night-cap danced again. "I am almost ready to sink, Ma'am, beneath the confusion of addressing a lady in my night-cap (here the lady hastily snatched off hers), but I can't get it off, Ma'am (here Mr. Pickwick gave it a tremendous tug, in proof of the statement). It is evident to me, Ma'am, now, that I have mistaken this bed-room for my own. I had not been here five minutes, Ma'am, when you suddenly entered it." "If this improbable story be really true, sir," said the lady, sobbing violently, "you will leave it instantly." "I will, Ma'am, with the greatest pleasure," replied Mr. Pickwick. "Instantly, sir," said the lady. "Certainly, Ma'am," interposed Mr. Pickwick very quickly. "Certainly, Ma'am. I - I - am very sorry, Ma'am,' said Mr. Pickwick, making his appearance at the bottom of the bed, "to have been the innocent occasion of this alarm and emotion; deeply sorry, Ma'am." The lady pointed to the door. One excellent quality of Mr. Pickwick's character was beautifully displayed at this moment, under the most trying circumstances. Although he had hastily put on his hat over his night-cap, after the manner of the old patrol; although he carried his shoes and gaiters in his hand, and his coat and waistcoat over his arm; nothing could subdue his native politeness. "I am exceedingly sorry, Ma'am," said Mr. Pickwick, bowing very low. "If you are, sir, you will at once leave the room," said the lady. "Immediately, Ma'am; this instant, Ma'am," said Mr. Pickwick, opening the door, and dropping both his shoes with a crash in so doing. "I trust, Ma'am," resumed Mr. Pickwick, gathering up his shoes, and turning round to bow again: "I trust, Ma'am, that my unblemished character, and the devoted respect I entertain for your sex, will plead as some slight excuse for this" - But before Mr. Pickwick could conclude the sentence the lady had thrust him into the passage, and locked and bolted the door behind him.

Oliver TwistCHAPTER XXXVII : IN WHICH THE READER MAY PERCEIVE A CONTRAST, NOT UNCOMMON IN MATRIMONIAL CASES

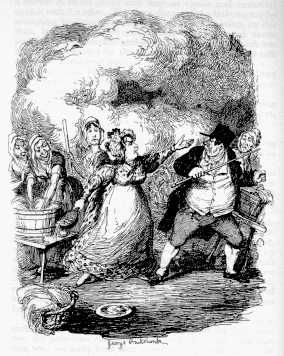

Mr. Bumle had married Mrs. Corney, and was master of the workhouse. Another beadle had come into power. On him the cocked hat, gold-laced coat, and staff, had all three descended. 'And to-morrow two months it was done!' said Mr. Bumble, with a sigh. 'It seems a age.' Mr. Bumble might have meant that he had concentrated a whole existence of happiness into the short space of eight weeks; but the sigh - there was a vast deal of meaning in the sigh. 'I sold myself,' said Mr. Bumble, pursuing the same train of reflection, 'for six teaspoons, a pair of sugar-tongs, and a milk-pot; with a small quantity of second-hand furniture, and twenty pound in money. I went very reasonable. Cheap, dirt cheap!' 'Cheap!' cried a shrill voice in Mr. Bumble's ear: 'you would have been dear at any price; and dear enough I paid for you, Lord above knows that!' Mr. Bumble turned, and encountered the face of his interesting consort, who, imperfectly comprehending the few words she had overheard of his complaint, had hazarded the foregoing remark at a venture. 'Mrs. Bumble, ma'am!' said Mr. Bumble, with a sentimental sternness. 'Well!' cried the lady. 'Have the goodness to look at me,' said Mr. Bumble, fixing his eyes upon her. (If she stands such a eye as that,' said Mr. Bumble to himself, 'she can stand anything. It is a eye I never knew to fail with paupers. If it fails with her, my power is gone.') Whether an exceedingly small expansion of eye be sufficient to quell paupers, who, being lightly fed, are in no very high condition; or whether the late Mrs. Corney was particularly proof against eagle glances; are matters of opinion. The matter of fact, is, that the matron was in no way overpowered by Mr. Bumble's scowl, but, on the contrary, treated it with great disdain, and even raised a laugh thereat, which sounded as though it were genuine. On hearing this most unexpected sound, Mr. Bumble looked, first incredulous, and afterwards amazed. He then relapsed into his former state; nor did he rouse himself until his attention was again awakened by the voice of his partner. 'Are you going to sit snoring there, all day?' inquired Mrs. Bumble. 'I am going to sit here, as long as I think proper, ma'am,' rejoined Mr. Bumble; 'and although I was NOT snoring, I shall snore, gape, sneeze, laugh, or cry, as the humour strikes me; such being my prerogative.' 'Your PREROGATIVE!' sneered Mrs. Bumble, with ineffable contempt. 'I said the word, ma'am,' said Mr. Bumble. 'The prerogative of a man is to command.' 'And what's the prerogative of a woman, in the name of Goodness?' cried the relict of Mr. Corney deceased. 'To obey, ma'am,' thundered Mr. Bumble. 'Your late unfortunate husband should have taught it you; and then, perhaps, he might have been alive now. I wish he was, poor man!' Mrs. Bumble, seeing at a glance, that the decisive moment had now arrived, and that a blow struck for the mastership on one side or other, must necessarily be final and conclusive, no sooner heard this allusion to the dead and gone, than she dropped into a chair, and with a loud scream that Mr. Bumble was a hard-hearted brute, fell into a paroxysm of tears. But, tears were not the things to find their way to Mr. Bumble's soul; his heart was waterproof. Like washable beaver hats that improve with rain, his nerves were rendered stouter and more vigorous, by showers of tears, which, being tokens of weakness, and so far tacit admissions of his own power, please and exalted him. He eyed his good lady with looks of great satisfaction, and begged, in an encouraging manner, that she should cry her hardest: the exercise being looked upon, by the faculty, as strongly conducive to health. 'It opens the lungs, washes the countenance, exercises the eyes, and softens down the temper,' said Mr. Bumble. 'So cry away.' As he discharged himself of this pleasantry, Mr. Bumble took his hat from a peg, and putting it on, rather rakishly, on one side, as a man might, who felt he had asserted his superiority in a becoming manner, thrust his hands into his pockets, and sauntered towards the door, with much ease and waggishness depicted in his whole appearance. Now, Mrs. Corney that was, had tried the tears, because they were less troublesome than a manual assault; but, she was quite prepared to make trial of the latter mode of proceeding, as Mr. Bumble was not long in discovering. The first proof he experienced of the fact, was conveyed in a hollow sound, immediately succeeded by the sudden flying off of his hat to the opposite end of the room. This preliminary proceeding laying bare his head, the expert lady, clasping him tightly round the throat with one hand, inflicted a shower of blows (dealt with singular vigour and dexterity) upon it with the other. This done, she created a little variety by scratching his face, and tearing his hair; and, having, by this time, inflicted as much punishment as she deemed necessary for the offence, she pushed him over a chair, which was luckily well situated for the purpose: and defied him to talk about his prerogative again, if he dared. 'Get up!' said Mrs. Bumble, in a voice of command. 'And take yourself away from here, unless you want me to do something desperate.' Mr. Bumble rose with a very rueful countenance: wondering much what something desperate might be. Picking up his hat, he looked towards the door. 'Are you going?' demanded Mr. Bumble. 'Certainly, my dear, certainly,' rejoined Mr. Bumble, making a quicker motion towards the door. 'I didn't intend to - I'm going, my dear! You are so very violent, that really I - ' At this instant, Mrs. Bumble stepped hastily forward to replace the carpet, which had been kicked up in the scuffle. Mr. Bumble immediately darted out of the room, without bestowing another thought on his unfinished sentence: leaving the late Mrs. Corney in full possession of the field. Mr. Bumble was fairly taken by surprise, and fairly beaten. He had a decided propensity for bullying: derived no inconsiderable pleasure from the exercise of petty cruelty; and, consequently, was (it is needless to say) a coward. This is by no means a disparagement to his character; for many official personages, who are held in high respect and admiration, are the victims of similar infirmities. The remark is made, indeed, rather in his favour than otherwise, and with a view of impressing the reader with a just sense of his qualifications for office. But, the measure of his degradation was not yet full. After making a tour of the house, and thinking, for the first time, that the poor-laws really were too hard on people; and that men who ran away from their wives, leaving them chargeable to the parish, ought, in justice to be visited with no punishment at all, but rather rewarded as meritorious individuals who had suffered much; Mr. Bumble came to a room where some of the female paupers were usually employed in washing the parish linen: when the sound of voices in conversation, now proceeded. 'Hem!' said Mr. Bumble, summoning up all his native dignity. 'These women at least shall continue to respect the prerogative. Hallo! hallo there! What do you mean by this noise, you hussies?' With these words, Mr. Bumble opened the door, and walked in with a very fierce and angry manner: which was at once exchanged for a most humiliated and cowering air, as his eyes unexpectedly rested on the form of his lady wife. 'My dear,' said Mr. Bumble, 'I didn't know you were here.' 'Didn't know I was here!' repeated Mrs. Bumble. 'What do YOU do here?' 'I thought they were talking rather too much to be doing their work properly, my dear,' replied Mr. Bumble: glancing distractedly at a couple of old women at the wash-tub, who were comparing notes of admiration at the workhouse-master's humility. 'YOU thought they were talking too much?' said Mrs. Bumble. 'What business is it of yours?' 'Why, my dear - ' urged Mr. Bumble submissively. 'What business is it of yours?' demanded Mrs. Bumble, again. 'It's very true, you're matron here, my dear,' submitted Mr. Bumble; 'but I thought you mightn't be in the way just then.' 'I'll tell you what, Mr. Bumble,' returned his lady. 'We don't want any of your interference. You're a great deal too fond of poking your nose into things that don't concern you, making everybody in the house laugh, the moment your back is turned, and making yourself look like a fool every hour in the day. Be off; come!' Mr. Bumble, seeing with excruciating feelings, the delight of the two old paupers, who were tittering together most rapturously, hesitated for an instant. Mrs. Bumble, whose patience brooked no delay, caught up a bowl of soap-suds, and motioning him towards the door, ordered him instantly to depart, on pain of receiving the contents upon his portly person. What could Mr. Bumble do? He looked dejectedly round, and slunk away; and, as he reached the door, the titterings of the paupers broke into a shrill chuckle of irrepressible delight. It wanted but this. He was degraded in their eyes; he had lost caste and station before the very paupers; he had fallen from all the height and pomp of beadleship, to the lowest depth of the most snubbed hen-peckery. 'All in two months!' said Mr. Bumble, filled with dismal thoughts. 'Two months! No more than two months ago, I was not only my own master, but everybody else's, so far as the porochial workhouse was concerned, and now! - '

Nicholas NicklebyCHAPTER XXXXLIX: MR. AND MRS. MANTALINI IN RALPH NICKLEBY'S OFFICE

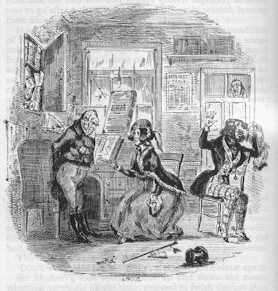

'Let me see the names,' replied Ralph, impatiently extending his hand for the bills. 'Well! They are not sure, but they are safe enough. Do you consent to the terms, and will you take the money? I don't want you to do so. I would rather you didn't.' 'Demmit, Nickleby, can't you -' began Mr Mantalini. 'No,' replied Ralph, interrupting him. 'I can't. Will you take the money - down, mind; no delay, no going into the City and pretending to negotiate with some other party who has no existence, and never had. Is it a bargain, or is it not?' Ralph pushed some papers from him as he spoke, and carelessly rattled his cash-box, as though by mere accident. The sound was too much for Mr Mantalini. He closed the bargain directly it reached his ears, and Ralph told the money out upon the table. He had scarcely done so, and Mr Mantalini had not yet gathered it all up, when a ring was heard at the bell, and immediately afterwards Newman ushered in no less a person than Madame Mantalini, at sight of whom Mr Mantalini evinced considerable discomposure, and swept the cash into his pocket with remarkable alacrity. 'Oh, you are here,' said Madame Mantalini, tossing her head. 'Yes, my life and soul, I am,' replied her husband, dropping on his knees, and pouncing with kitten-like playfulness upon a stray sovereign. 'I am here, my soul's delight, upon Tom Tidler's ground, picking up the demnition gold and silver.' 'I am ashamed of you,' said Madame Mantalini, with much indignation. 'Ashamed - of me, my joy? It knows it is talking demd charming sweetness, but naughty fibs,' returned Mr Mantalini. 'It knows it is not ashamed of its own popolorum tibby.' Whatever were the circumstances which had led to such a result, it certainly appeared as though the popolorum tibby had rather miscalculated, for the nonce, the extent of his lady's affection. Madame Mantalini only looked scornful in reply; and, turning to Ralph, begged him to excuse her intrusion. 'Which is entirely attributable,' said Madame, 'to the gross misconduct and most improper behaviour of Mr Mantalini.' 'Of me, my essential juice of pineapple!' 'Of you,' returned his wife. 'But I will not allow it. I will not submit to be ruined by the extravagance and profligacy of any man. I call Mr Nickleby to witness the course I intend to pursue with you.' 'Pray don't call me to witness anything, ma'am,' said Ralph. 'Settle it between yourselves, settle it between yourselves.' 'No, but I must beg you as a favour,' said Madame Mantalini, 'to hear me give him notice of what it is my fixed intention to do - my fixed intention, sir,' repeated Madame Mantalini, darting an angry look at her husband. 'Will she call me "Sir"?' cried Mantalini. 'Me who dote upon her with the demdest ardour! She, who coils her fascinations round me like a pure angelic rattlesnake! It will be all up with my feelings; she will throw me into a demd state.' 'Don't talk of feelings, sir,' rejoined Madame Mantalini, seating herself, and turning her back upon him. 'You don't consider mine.' 'I do not consider yours, my soul!' exclaimed Mr Mantalini. 'No,' replied his wife. And notwithstanding various blandishments on the part of Mr Mantalini, Madame Mantalini still said no, and said it too with such determined and resolute ill-temper, that Mr Mantalini was clearly taken aback. 'His extravagance, Mr Nickleby,' said Madame Mantalini, addressing herself to Ralph, who leant against his easy-chair with his hands behind him, and regarded the amiable couple with a smile of the supremest and most unmitigated contempt, - 'his extravagance is beyond all bounds.' 'I should scarcely have supposed it,' answered Ralph, sarcastically. 'I assure you, Mr Nickleby, however, that it is,' returned Madame Mantalini. 'It makes me miserable! I am under constant apprehensions, and in constant difficulty. And even this,' said Madame Mantalini, wiping her eyes, 'is not the worst. He took some papers of value out of my desk this morning without asking my permission.' Mr Mantalini groaned slightly, and buttoned his trousers pocket. 'I am obliged,' continued Madame Mantalini, 'since our late misfortunes, to pay Miss Knag a great deal of money for having her name in the business, and I really cannot afford to encourage him in all his wastefulness. As I have no doubt that he came straight here, Mr Nickleby, to convert the papers I have spoken of, into money, and as you have assisted us very often before, and are very much connected with us in this kind of matters, I wish you to know the determination at which his conduct has compelled me to arrive.' Mr Mantalini groaned once more from behind his wife's bonnet, and fitting a sovereign into one of his eyes, winked with the other at Ralph. Having achieved this performance with great dexterity, he whipped the coin into his pocket, and groaned again with increased penitence. 'I have made up my mind,' said Madame Mantalini, as tokens of impatience manifested themselves in Ralph's countenance, 'to allowance him.' 'To do that, my joy?' inquired Mr Mantalini, who did not seem to have caught the words. 'To put him,' said Madame Mantalini, looking at Ralph, and prudently abstaining from the slightest glance at her husband, lest his many graces should induce her to falter in her resolution, 'to put him upon a fixed allowance; and I say that if he has a hundred and twenty pounds a year for his clothes and pocket-money, he may consider himself a very fortunate man.' Mr Mantalini waited, with much decorum, to hear the amount of the proposed stipend, but when it reached his ears, he cast his hat and cane upon the floor, and drawing out his pocket-handkerchief, gave vent to his feelings in a dismal moan. 'Demnition!' cried Mr Mantalini, suddenly skipping out of his chair, and as suddenly skipping into it again, to the great discomposure of his lady's nerves. 'But no. It is a demd horrid dream. It is not reality. No!' Comforting himself with this assurance, Mr Mantalini closed his eyes and waited patiently till such time as he should wake up. 'A very judicious arrangement,' observed Ralph with a sneer, 'if your husband will keep within it, ma'am - as no doubt he will.' 'Demmit!' exclaimed Mr Mantalini, opening his eyes at the sound of Ralph's voice, 'it is a horrid reality. She is sitting there before me. There is the graceful outline of her form; it cannot be mistaken - there is nothing like it. The two countesses had no outlines at all, and the dowager's was a demd outline. Why is she so excruciatingly beautiful that I cannot be angry with her, even now?' 'You have brought it upon yourself, Alfred,' returned Madame Mantalini - still reproachfully, but in a softened tone. 'I am a demd villain!' cried Mr Mantalini, smiting himself on the head. 'I will fill my pockets with change for a sovereign in halfpence and drown myself in the Thames; but I will not be angry with her, even then, for I will put a note in the twopenny-post as I go along, to tell her where the body is. She will be a lovely widow. I shall be a body. Some handsome women will cry; she will laugh demnebly.' 'Alfred, you cruel, cruel creature,' said Madame Mantalini, sobbing at the dreadful picture. 'She calls me cruel - me - me - who for her sake will become a demd, damp, moist, unpleasant body!' exclaimed Mr Mantalini. 'You know it almost breaks my heart, even to hear you talk of such a thing,' replied Madame Mantalini. 'Can I live to be mistrusted?' cried her husband. 'Have I cut my heart into a demd extraordinary number of little pieces, and given them all away, one after another, to the same little engrossing demnition captivater, and can I live to be suspected by her? Demmit, no I can't.' 'Ask Mr Nickleby whether the sum I have mentioned is not a proper one,' reasoned Madame Mantalini. 'I don't want any sum,' replied her disconsolate husband; 'I shall require no demd allowance. I will be a body.' On this repetition of Mr Mantalini's fatal threat, Madame Mantalini wrung her hands, and implored the interference of Ralph Nickleby; and after a great quantity of tears and talking, and several attempts on the part of Mr Mantalini to reach the door, preparatory to straightway committing violence upon himself, that gentleman was prevailed upon, with difficulty, to promise that he wouldn't be a body. This great point attained, Madame Mantalini argued the question of the allowance, and Mr Mantalini did the same, taking occasion to show that he could live with uncommon satisfaction upon bread and water, and go clad in rags, but that he could not support existence with the additional burden of being mistrusted by the object of his most devoted and disinterested affection. This brought fresh tears into Madame Mantalini's eyes, which having just begun to open to some few of the demerits of Mr Mantalini, were only open a very little way, and could be easily closed again. The result was, that without quite giving up the allowance question, Madame Mantalini, postponed its further consideration; and Ralph saw, clearly enough, that Mr Mantalini had gained a fresh lease of his easy life, and that, for some time longer at all events, his degradation and downfall were postponed.

The Old Curiosity ShopCHAPTER XLIX: A DESCRIPTIVE ADVERTISEMENT

The bedroom-door on the staircase being unlocked, Mr Quilp slipped in, and planted himself behind the door of communication between that chamber and the sitting-room, which standing ajar to render both more airy, and having a very convenient chink (of which he had often availed himself for purposes of espial, and had indeed enlarged with his pocket-knife), enabled him not only to hear, but to see distinctly, what was passing. Applying his eye to this convenient place, he descried Mr Brass seated at the table with pen, ink, and paper, and the case-bottle of rum - his own case-bottle, and his own particular Jamaica - convenient to his hand; with hot water, fragrant lemons, white lump sugar, and all things fitting; from which choice materials, Sampson, by no means insensible to their claims upon his attention, had compounded a mighty glass of punch reeking hot; which he was at that very moment stirring up with a teaspoon, and contemplating with looks in which a faint assumption of sentimental regret, struggled but weakly with a bland and comfortable joy. At the same table, with both her elbows upon it, was Mrs Jiniwin; no longer sipping other people's punch feloniously with teaspoons, but taking deep draughts from a jorum of her own; while her daughter - not exactly with ashes on her head, or sackcloth on her back, but preserving a very decent and becoming appearance of sorrow nevertheless - was reclining in an easy chair, and soothing her grief with a smaller allowance of the same glib liquid. There were also present, a couple of water-side men, bearing between them certain machines called drags; even these fellows were accommodated with a stiff glass a-piece; and as they drank with a great relish, and were naturally of a red-nosed, pimple-faced, convivial look, their presence rather increased than detracted from that decided appearance of comfort, which was the great characteristic of the party. 'If I could poison that dear old lady's rum and water,' murmured Quilp, 'I'd die happy.' 'Ah!' said Mr Brass, breaking the silence, and raising his eyes to the ceiling with a sigh, 'Who knows but he may be looking down upon us now! Who knows but he may be surveying of us from - from somewheres or another, and contemplating us with a watchful eye! Oh Lor!' Here Mr Brass stopped to drink half his punch, and then resumed; looking at the other half, as he spoke, with a dejected smile. 'I can almost fancy,' said the lawyer shaking his head, 'that I see his eye glistening down at the very bottom of my liquor. When shall we look upon his like again? Never, never!' One minute we are here' - holding his tumbler before his eyes - 'the next we are there' - gulping down its contents, and striking himself emphatically a little below the chest - 'in the silent tomb. To think that I should be drinking his very rum! It seems like a dream.' With the view, no doubt, of testing the reality of his position, Mr Brass pushed his tumbler as he spoke towards Mrs Jiniwin for the purpose of being replenished; and turned towards the attendant mariners. 'The search has been quite unsuccessful then?' 'Quite, master. But I should say that if he turns up anywhere, he'll come ashore somewhere about Grinidge to-morrow, at ebb tide, eh, mate?' The other gentleman assented, observing that he was expected at the Hospital, and that several pensioners would be ready to receive him whenever he arrived. 'Then we have nothing for it but resignation,' said Mr Brass; 'nothing but resignation and expectation. It would be a comfort to have his body; it would be a dreary comfort.' 'Oh, beyond a doubt,' assented Mrs Jiniwin hastily; 'if we once had that, we should be quite sure.' 'With regard to the descriptive advertisement,' said Sampson Brass, taking up his pen. 'It is a melancholy pleasure to recall his traits. Respecting his legs now -?' 'Crooked, certainly,' said Mrs Jiniwin. 'Do you think they WERE crooked?' said Brass, in an insinuating tone. 'I think I see them now coming up the street very wide apart, in nankeen' pantaloons a little shrunk and without straps. Ah! what a vale of tears we live in. Do we say crooked?' 'I think they were a little so,' observed Mrs Quilp with a sob. 'Legs crooked,' said Brass, writing as he spoke. 'Large head, short body, legs crooked -' Very crooked,' suggested Mrs Jiniwin. 'We'll not say very crooked, ma'am,' said Brass piously. 'Let us not bear hard upon the weaknesses of the deceased. He is gone, ma'am, to where his legs will never come in question. - We will content ourselves with crooked, Mrs Jiniwin.' 'I thought you wanted the truth,' said the old lady. 'That's all.' 'Bless your eyes, how I love you,' muttered Quilp. 'There she goes again. Nothing but punch!' 'This is an occupation,' said the lawyer, laying down his pen and emptying his glass, 'which seems to bring him before my eyes like the Ghost of Hamlet's father, in the very clothes that he wore on work-a-days. His coat, his waistcoat, his shoes and stockings, his trousers, his hat, his wit and humour, his pathos and his umbrella, all come before me like visions of my youth. His linen!' said Mr Brass smiling fondly at the wall, 'his linen which was always of a particular colour, for such was his whim and fancy - how plain I see his linen now!' 'You had better go on, sir,' said Mrs Jiniwin impatiently. 'True, ma'am, true,' cried Mr Brass. 'Our faculties must not freeze with grief. I'll trouble you for a little more of that, ma'am. A question now arises, with relation to his nose.' 'Flat,' said Mrs Jiniwin. 'Aquiline!' cried Quilp, thrusting in his head, and striking the feature with his fist. 'Aquiline, you hag. Do you see it? Do you call this flat? Do you? Eh?' 'Oh capital, capital!' shouted Brass, from the mere force of habit. 'Excellent! How very good he is! He's a most remarkable man - so extremely whimsical! Such an amazing power of taking people by surprise!' Quilp paid no regard whatever to these compliments, nor to the dubious and frightened look into which the lawyer gradually subsided, nor to the shrieks of his wife and mother-in-law, nor to the latter's running from the room, nor to the former's fainting away. Keeping his eye fixed on Sampson Brass, he walked up to the table, and beginning with his glass, drank off the contents, and went regularly round until he had emptied the other two, when he seized the case-bottle, and hugging it under his arm, surveyed him with a most extraordinary leer. 'Not yet, Sampson,' said Quilp. 'Not just yet!' 'Oh very good indeed!' cried Brass, recovering his spirits a little. 'Ha ha ha! Oh exceedingly good! There's not another man alive who could carry it off like that. A most difficult position to carry off. But he has such a flow of good-humour, such an amazing flow!' 'Good night,' said the dwarf, nodding expressively. 'Good night, sir, good night,' cried the lawyer, retreating backwards towards the door. 'This is a joyful occasion indeed, extremely joyful. Ha ha ha! oh very rich, very rich indeed, remarkably so!' Waiting until Mr Brass's ejaculations died away in the distance (for he continued to pour them out, all the way down stairs), Quilp advanced towards the two men, who yet lingered in a kind of stupid amazement. 'Have you been dragging the river all day, gentlemen?' said the dwarf, holding the door open with great politeness. 'And yesterday too, master.' 'Dear me, you've had a deal of trouble. Pray consider everything yours that you find upon the - upon the body. Good night!' The men looked at each other, but had evidently no inclination to argue the point just then, and shuffled out of the room. The speedy clearance effected, Quilp locked the doors; and still embracing the case-bottle with shrugged-up shoulders and folded arms, stood looking at his insensible wife like a dismounted nightmare.

Barnaby RudgeCHAPTER IV: IT'S A POOR HEART THAT NEVER REJOICES

'Hush!' she whispered, bending forward and pointing archly to the window underneath. 'Mother is still asleep.' 'Still, my dear,' returned the locksmith in the same tone. 'You talk as if she had been asleep all night, instead of little more than half an hour. But I'm very thankful. Sleep's a blessing - no doubt about it.' The last few words he muttered to himself. 'How cruel of you to keep us up so late this morning, and never tell us where you were, or send us word!' said the girl. 'Ah Dolly, Dolly!' returned the locksmith, shaking his head, and smiling, 'how cruel of you to run upstairs to bed! Come down to breakfast, madcap, and come down lightly, or you'll wake your mother. She must be tired, I am sure - I am.' Keeping these latter words to himself, and returning his daughter's nod, he was passing into the workshop, with the smile she had awakened still beaming on his face, when he just caught sight of his 'prentice's brown paper cap ducking down to avoid observation, and shrinking from the window back to its former place, which the wearer no sooner reached than he began to hammer lustily. 'Listening again, Simon!' said Gabriel to himself. 'That's bad. What in the name of wonder does he expect the girl to say, that I always catch him listening when SHE speaks, and never at any other time! A bad habit, Sim, a sneaking, underhanded way. Ah! you may hammer, but you won't beat that out of me, if you work at it till your time's up!' So saying, and shaking his head gravely, he re-entered the workshop, and confronted the subject of these remarks. 'There's enough of that just now,' said the locksmith. 'You needn't make any more of that confounded clatter. Breakfast's ready.' 'Sir,' said Sim, looking up with amazing politeness, and a peculiar little bow cut short off at the neck, 'I shall attend you immediately.' 'I suppose,' muttered Gabriel, 'that's out of the 'Prentice's Garland or the 'Prentice's Delight, or the 'Prentice's Warbler, or the Prentice's Guide to the Gallows, or some such improving textbook. Now he's going to beautify himself - here's a precious locksmith!' Quite unconscious that his master was looking on from the dark corner by the parlour door, Sim threw off the paper cap, sprang from his seat, and in two extraordinary steps, something between skating and minuet dancing, bounded to a washing place at the other end of the shop, and there removed from his face and hands all traces of his previous work - practising the same step all the time with the utmost gravity. This done, he drew from some concealed place a little scrap of looking-glass, and with its assistance arranged his hair, and ascertained the exact state of a little carbuncle on his nose. Having now completed his toilet, he placed the fragment of mirror on a low bench, and looked over his shoulder at so much of his legs as could be reflected in that small compass, with the greatest possible complacency and satisfaction. Sim, as he was called in the locksmith's family, or Mr Simon Tappertit, as he called himself, and required all men to style him out of doors, on holidays, and Sundays out, - was an old-fashioned, thin-faced, sleek-haired, sharp-nosed, small-eyed little fellow, very little more than five feet high, and thoroughly convinced in his own mind that he was above the middle size; rather tall, in fact, than otherwise. Of his figure, which was well enough formed, though somewhat of the leanest, he entertained the highest admiration; and with his legs, which, in knee-breeches, were perfect curiosities of littleness, he was enraptured to a degree amounting to enthusiasm. He also had some majestic, shadowy ideas, which had never been quite fathomed by his intimate friends, concerning the power of his eye. Indeed he had been known to go so far as to boast that he could utterly quell and subdue the haughtiest beauty by a simple process, which he termed 'eyeing her over;' but it must be added, that neither of this faculty, nor of the power he claimed to have, through the same gift, of vanquishing and heaving down dumb animals, even in a rabid state, had he ever furnished evidence which could be deemed quite satisfactory and conclusive. It may be inferred from these premises, that in the small body of Mr Tappertit there was locked up an ambitious and aspiring soul. As certain liquors, confined in casks too cramped in their dimensions, will ferment, and fret, and chafe in their imprisonment, so the spiritual essence or soul of Mr Tappertit would sometimes fume within that precious cask, his body, until, with great foam and froth and splutter, it would force a vent, and carry all before it. It was his custom to remark, in reference to any one of these occasions, that his soul had got into his head; and in this novel kind of intoxication many scrapes and mishaps befell him, which he had frequently concealed with no small difficulty from his worthy master. Sim Tappertit, among the other fancies upon which his before- mentioned soul was for ever feasting and regaling itself (and which fancies, like the liver of Prometheus, grew as they were fed upon), had a mighty notion of his order; and had been heard by the servant-maid openly expressing his regret that the 'prentices no longer carried clubs wherewith to mace the citizens: that was his strong expression. He was likewise reported to have said that in former times a stigma had been cast upon the body by the execution of George Barnwell, to which they should not have basely submitted, but should have demanded him of the legislature - temperately at first; then by an appeal to arms, if necessary - to be dealt with as they in their wisdom might think fit. These thoughts always led him to consider what a glorious engine the 'prentices might yet become if they had but a master spirit at their head; and then he would darkly, and to the terror of his hearers, hint at certain reckless fellows that he knew of, and at a certain Lion Heart ready to become their captain, who, once afoot, would make the Lord Mayor tremble on his throne. In respect of dress and personal decoration, Sim Tappertit was no less of an adventurous and enterprising character. He had been seen, beyond dispute, to pull off ruffles of the finest quality at the corner of the street on Sunday nights, and to put them carefully in his pocket before returning home; and it was quite notorious that on all great holiday occasions it was his habit to exchange his plain steel knee-buckles for a pair of glittering paste, under cover of a friendly post, planted most conveniently in that same spot. Add to this that he was in years just twenty, in his looks much older, and in conceit at least two hundred; that he had no objection to be jested with, touching his admiration of his master's daughter; and had even, when called upon at a certain obscure tavern to pledge the lady whom he honoured with his love, toasted, with many winks and leers, a fair creature whose Christian name, he said, began with a D --; - and as much is known of Sim Tappertit, who has by this time followed the locksmith in to breakfast, as is necessary to be known in making his acquaintance. It was a substantial meal; for, over and above the ordinary tea equipage, the board creaked beneath the weight of a jolly round of beef, a ham of the first magnitude, and sundry towers of buttered Yorkshire cake, piled slice upon slice in most alluring order. There was also a goodly jug of well-browned clay, fashioned into the form of an old gentleman, not by any means unlike the locksmith, atop of whose bald head was a fine white froth answering to his wig, indicative, beyond dispute, of sparkling home-brewed ale. But, better far than fair home-brewed, or Yorkshire cake, or ham, or beef, or anything to eat or drink that earth or air or water can supply, there sat, presiding over all, the locksmith's rosy daughter, before whose dark eyes even beef grew insignificant, and malt became as nothing. Fathers should never kiss their daughters when young men are by. It's too much. There are bounds to human endurance. So thought Sim Tappertit when Gabriel drew those rosy lips to his - those lips within Sim's reach from day to day, and yet so far off. He had a respect for his master, but he wished the Yorkshire cake might choke him.

Top of Page Top of Page  Mitsuharu Matsuoka's Home Page Mitsuharu Matsuoka's Home Page

|